art-Renoir.com

Auguste Renoir 1841-1919

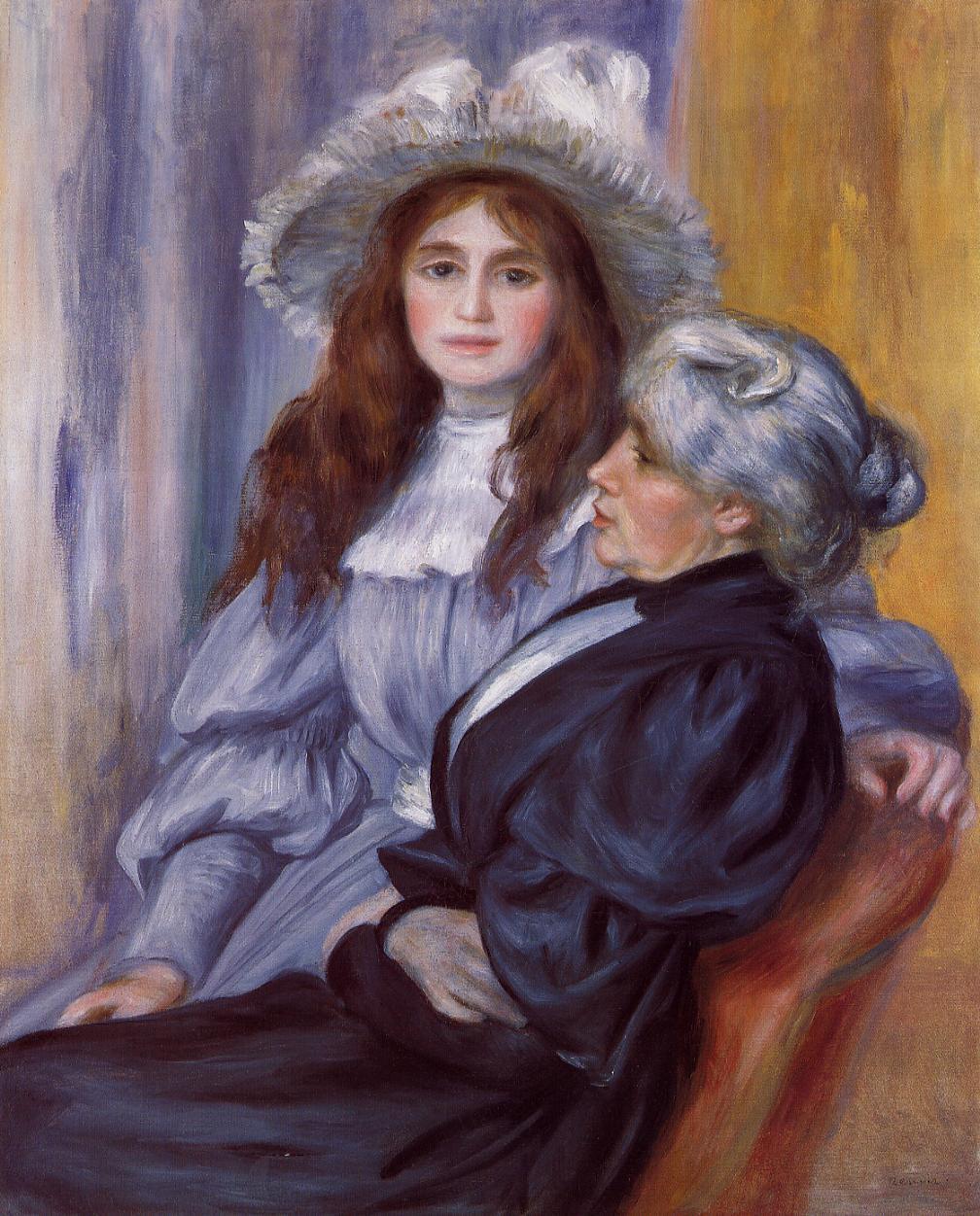

Auguste Renoir - Berthe Morisot and her daughter Julie Manet 1894

Berthe Morisot and her daughter Julie Manet |

From Christie's auction house:

This remarkable double portrait is a masterpiece from Pierre-Auguste Renoir's later oeuvre and an icon of the Impressionist movement. Painted in 1894, the present work is not only a rare 'family snapshot,' but a visual document of the friendship between Renoir and Morisot, a friendship that Renoir would refer to as "one of the most solid of my life" (quoted in C. Bailey, ed., Renoir's Portraits, Impressions of an Age, exh. cat, Milan, 1997, p. 220). Recently included in the exhibition Renoirs Portraits, Impressions of an Age, the present work is a tour de force that epitomizes Renoir's talent as a portrait painter.

Although women were not formally admitted into the Ecole des Beaux-Arts until the late nineteenth century, as a member of the haute bourgeoisie, Berthe Morisot received private art lessons. Her talent apparent from an early age, she became perhaps the most privileged female painters in Parisian society developing close social and professional relationships with artists such as Henri Fantin-Latour and Pierre Puvis de Chavannes. After studying under Camille Corot in the 1860s, she became Edouard Manet's model and protégé. Morisot's marriage in 1874 to Eugène Manet, Edouard's brother, would further secure her position within the Impressionist circle. Berthe is portrayed in Edouard Manet's 1870 painting Repos (W.158) as a young and confident artist approaching the height of her professional career. The attention Berthe received provoked a jealous comment from her sister Edma who once remarked, "Your life must be charming at this moment, to talk with M. Degas while watching him draw, to laugh with Manet, to philosophize with Puvis" (quoted in C.F. Stuckey and W. P. Scott, Berthe Morisot, Impressionist, New York, 1987, p. 28).

An exhibitor in seven of the eight Impressionist exhibitions, Berthe Morisot was one of the most loyal artists to support the Impressionist movement. During a time when women artists struggled to gain acceptance and recognition, she won the respect of Renoir and other well-established artists early on when in 1877 Renoir and Gustave Caillebotte invited her to the Third Impressionist exhibit. But it was not until the winter of 1886, when Morisot began making trips to Renoir's studio, that their friendship began to fully develop. The two artists influenced each other stylistically, their social circles began to merge and the two families frequently vacationed together. Their combined circle of friends encompassed some of the most important figures in the Impressionist community such as the poet Stéphane Mallarmé, (fig. 1) the writer Henri de Régnier, fellow painters Mary Cassatt, Alfred Sisley, Claude Monet, Edouard Manet and of course, Pierre-Auguste Renoir. Morisot's famous Thursday soirées first at the family home in rue de Villejust, and after Eugène's death in Morisot's new home in the rue Weber, became a frequent gathering spot for the rapidly growing 'Impressionist family.' In Renoir, my father, Renoir's son Jean recalls how much his father enjoyed these evenings:

In Berthe Morisot's day, the Manet circle had been one of the most authentic centers of civilized Parisian life... he [Renoir] loved spending an hour or two at the house in Rue de Villejust. It was not the intellectuals one met at Berthe Morisot's, but simply good company . . . Berthe Morisot acted like a special kind of magnet on people, attracting only the genuine. She had a gift for smoothing out the rough edges. 'Even Degas became more civil with her. The little Manet girls', as they were called, carried on the family tradition. And when Rouart and Valéry married into the family, it was further enriched (J. Renoir, Renoir, my father, London, 1962, p. 269).

During a period when there was an increasing demand for higher prices by Impressionist artists, Renoir offered to introduce Berthe to his friends and powerful Parisian dealers at various dinner parties. On March 31, 1894 he wrote:

Next Wednesday Mallarmé is giving me the pleasure of coming to dinner in Montmartre. If climbing up here in the evening is not too arduous for you, I thought he might enjoy meeting you here. There will also be Durand-Ruel, and I am going to write the above-mentioned poet to ask him to invite de Régnier for me. P.S. - I don't mention the sweet and lovely Julie; it goes without saying, and I think that Mallarmé is bringing his daughter. I wanted to ask Degas, but I confess I don't dare (B.E. White, op. cit., p. 200).

Morisot's only child, Julie Manet was born in 1878. Immortalized in paintings both by Renoir and Morisot, she became the daughter of the Impressionist community and thus a symbol of the times. Their strong mother-daughter bond made them inseparable. In one of her diaries, she recalls an afternoon in the park with Julie: "I walk with Julie in Paris. We sit down, me thinking of my painting of a garden, looking at the shadows that play across the sand and the roofs of the Louvre. I search with her the relation of the shadows and the sunlight. She sees pink in the sunlight, purple in the shadows" (Berthe Morisot's notebook, 1885).

Renoir, who held a special fondness for Julie, painted a portrait of the nine-year old girl in 1887. It was in 1894, the same year that Renoir began a single portrait of Julie Manet, that the idea came to Renoir to invite Morisot to sit a double portrait with her daughter. In April of 1894, Renoir wrote to Morisot:

If you do not mind, I should like to, instead of painting, Julie alone, to paint her with you. But this is what bothers me: if I were to plan to work at your house, something will always turn up to keep me from coming. On the other hand if you are willing to give me two hours, that is, two mornings or afternoons a week, I think I can do the portrait in six sessions at the most. Tell me, is it yes or no? (D. Rouart, ed., Berthe Morisot, The correspondence with her family and friends, Devon, 1987, p. 205).

Morisot agreed to his request and the two sat for the portrait in Renoir's studio at 7 rue Tourlaque. These live sittings became a sort of "family affair" and were always followed by lunch at Renoir's house. The date of the sitting is usually placed in early April. Due to the rapidity with which Renoir worked combined with the fact that he was in the south of France for health reasons in mid-April, it is likely that the portrait was finished in under a week. Renoir first sketched a preparatory pastel study (fig. 2), later gifted to the Petit Palais in Paris by Renoir in 1908. In the sketch, Renoir remained true to the basic composition, but extended it vertically to place greater emphasis on Julie.

The double portrait is as much a personal diary of the artist and his close relationship with the sitters, as it is a portrait of mother and child. In the present composition, Renoir captures the same expression and stance that Julie displays in a contemporary photograph (fig. 3). Similarly, when compared with her likeness in the portrait, a recent photograph of Berthe (fig. 4) shows Renoir's "unerring fidelity for appearances" (C. Bailey, op. cit., p. 223). Now an elderly lady, Morisot, the 'Grande Dame' of Impressionism sits regally in profile.

In the positioning of his figures, Renoir adopts an overlapping format that is "rare in his oeuvre but quite frequent in Morisot's" (ibid., p. 220). He most likely borrowed this format from Morisot's, The Children of Gabriel Thomas of the same year where two figures are shown in a unusual juxtaposition. (C.F. Stuckey and M.P. Scott, op. cit., pl. 102). A distinctive feature of Renoir's later work is his more muted palette of colors, linked to his desire to find "a definitive, simple range of colors for his palette that would serve his every need, in his obsessive concern for mastering the art of painting"(M. Raeburn, ed., exh. cat., Renoir, Hayward Gallery, Rugby, 1984, p. 250). Masterfully blended, his brushstrokes are airy and delicate, particularly evident in the rainbow-streaked background and the treatment of the figures.

As requested in Morisot's will, Renoir became Julie's guardian after her passing on March 2, 1895, a true testimony of their friendship. Julie remembers Renoir's reaction; "he was in the midst of painting alongside Cézanne when he learned of Mother's death, he closed his paint box and took the train - I have never forgotten the way he came into my room on the rue Weber and took me in his arms - I can still see his white flowing necktie with red polka dots." (B.E. White, op. cit., p. 201). Although she lived with her two orphaned cousins, Jeanne and Paul Gobillard, all three of them spent July and August at the Renoir's summer home in Brittany and took painting lessons from the master. In a diary entry of October 4, 1895, only a few months after her mother's death, Julie speaks of the Renoir family's kindness. She writes, "We are leaving the Renoirs, M. Renoir who has been so kind and charming all summer; the more one sees of him, the more one finds him an artist, fine and of an extraordinary intelligence, but on top of that with a sincere simplicity" (ibid., p. 201).

In March of 1896, the seventeen year old Julie organized an exhibition of over three hundred of her mother's works at Durand-Ruel's Paris Gallery, a show which received much critical acclaim. Julie Manet married the painter Ernest Rouart on May 29, 1900 "a match engineered by Degas" (C. Bailey, op. cit., p. 223). Just as Julie followed her mother in her own ambition to become a painter, so this painting, which has remained in the Rouart family ever since 1894, represents part of the family's important legacy.